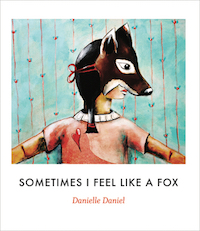

Fairy Tales & Fables Part 1: Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Billy Goats Gruff, & The Three Little Pigs

There are so many reasons for parents to read fairy tales and fables to young

Once upon a time, I imagined my twins inundating me with why? questions. “Ugh. Luke and Harry have entered the “why?” phase!” I’d complain, playing my part.

My reality is a little different. My kids are now 4 year olds, with autism and language delays, and they've never once asked me why?. "W-questions" are the stuff of IEP goals.

Lately, I've been fretting a lot about the importance of why. Before having kids, I was very active in progressive politics, and now I'm trying to re-emerge and play my part in the resistance against Trump. One small way I do this is by participating in parenting conversations among fellow progressives about how to raise our children in this new, uncertain America. But my issues are complicated by disability: How does one communicate a because to a child who can't ask why?

I lay awake at night trying to figure it out. Should I teach Luke and Harry what race is?, I've wondered. I imagine myself with a spread of flash cards with differently shaded faces and feel sick. Progressive parents are supposed to spend their time deconstructing social constructs, not building them up, right? But on the other hand, typically developing children naturally acquire this language. Mine don't, or at least this process is very delayed. I've learned to challenge other white people who deny the reality of racism, professing "colorblindness." Am I any better if I leave my own children in a state of ignorance of race?

Depressingly, there isn't a lot of academic scholarship out there to guide parents and educators. One study found that when children with autism reach a “verbal age of 6 or 7 years old,” they will have absorbed gender and race stereotypes just as readily as their typically developing peers. Understanding stereotypes is obviously a prerequisite to being able to think critically about social categories, and it is also important for children with autism themselves. You need to understand society to function within it.

But of course, "absorbing stereotypes" barely scratches the surface of what I'm getting at here. What impact does it have on kids with autism to develop awareness of race and gender stereotypes separately from a typically developing peer group? How do their different learning styles impact what they learn? How about kids who are more socially delayed but who may have closer to typical language skills? What happens to kids who take a considerably longer time to reach a "verbal age of 6 or 7"—or to those who remain completely or nearly nonverbal? What about kids with co-morbid intellectual disabilities? How about development of racial identity? How is this learning experience different based on the child's race? What about learning how to challenge stereotyped thinking once its learned?

These are so many unanswered questions! And it's extra frustrating, because with typically developing children, there is endless research to cite, and we understand this developmental process decently well. We know, for instance, that neurotypical kids become aware of the social idea of race by 4 (and gender even earlier than that). Long before the chronological age of 6 or 7, they are using language to try out the stereotypes they pick up on, gaining invaluable information from the responses of grown-ups and peers. They can also ask why? why? why? why?, perhaps annoying the crap out of their parents, but also uncovering nuance, discovering contradictions, and gaining access to learning opportunities that allow them to better puzzle over social tensions in their cultural environment. Put more succinctly: Once kids have the words, they can think about the ideas.

Our comparatively robust knowledge about how typically developing kids learn about social categories, buttressed by hundreds of studies and published articles in the last ten years alone, has resulted in a growing drumbeat amongst progressive educators in favor of deliberate anti-bias education that doesn't shy away from confronting oppressive structures, but rather supports children, guiding their developing awareness.

And so the gap between what progressive people are doing to prepare typically developing children to be tomorrow's citizens and what we do for developmentally delayed children seems to grow incalculably, irresponsibly, wide.

Where does that leave progressive me? Not so unlike other parents, particularly white parents, who have had to learn to stomach the idea of teaching typically developing kids explicitly about racism and ethnic bias, I'm coming around to the idea that my autistic kids must be actively taught to understand what race and ethnicity are and to learn the language of difference.

Many of the parents of older kids with ASD and special educators I spoke to about how to do this told me that absent specific research, a natural approach using carefully chosen books is my best bet. I'm worried that it may not be enough for Luke, who still needs discrete trial training (DTT) to learn new and difficult concepts—but I'm giving it my best effort!

This is my second post in a special series of blog posts featuring progressive picture books for children with autism. In part one, "This Land Was Made for You and Me," I highlighted books with broadly progressive themes. This time, I've targeted books that can be used to introduce some of the language of race and ethnicity. (I plan to do a separate post on books positively representing world religions and their holidays, especially Muslims and Islamic culture, later this year.)

In developing this list, I made good use of the invaluable online resource We Need Diverse Books. This was an excellent starting place, even though they don't look at books with an eye to accessibility. All in all, I tested out 94 books with my (remarkably cooperative) kids. These were the 10 that really clicked.

Chronicle Books (2014); hardcover, $16.99

Suggested target concept/words: Spanish, language

So many other books I looked at for introducing the idea of there being other languages (specifically highlighting the Spanish language) lacked a really strong structure, which is extra important when demanding a child absorb a difficult language-based concept.

But Green is a Chile Pepper: A Book of Colors was a home-run. It has the familiar format of a color primer (This page has things that are blue; this one has things that are green, etc.), and introduces Mexican/Mexican-American cultural objects in an accessible way by blending the specific with the universal in visually engaging scenes of everyday life.

Because very young children with autism almost always do color programs in the early days of ABA therapy, color primer books are ideal for generalizing or maintaining these skills. Color primers are also pleasurable for a child who has mastered their colors and has therefore learned to enjoy being praised for identifying them correctly. This is certainly the case for my son Luke, who easily attended to this book, excited for the opportunity to label colors.

Luke is currently working on the goal of expanding utterances with his speech therapist using color as a modifier, so instead of labeling pink or learning what a piñata is, I have him practice saying pink piñata. For my son Harry, who is a little further ahead in his language development, the idea of different words for colors is of interest (red/rojo, etc.). He echoed my explanation: "Rojo is red in Spanish." And I think this is a great place to start for him.

Each color scene has a lot of things to look at that are both familiar and potentially unfamiliar. (For a child from a home where Spanish is spoken or for a child from Mexico, there would obviously be much more to personally connect with.) On the first red page, for instance, two children and their mother are in a kitchen. A ristra hangs from the ceiling, and the girl holds one too. Red peppers are things my kids have seen before, but not ristra, which, I learned, are bundles of dried red chiles. (There is a glossary at the back of the book for parents like me who need help here.) On the more familiar end of things, the boy holds a plate of rice with red salsa. Finally, there are the more obvious red things that help anchor a child: red roses, a cat chasing a red ball of yarn, and the people themselves who are wearing red clothes. The art is bright, engaging, and has a warm folk art appeal.

Red is a ristra

Red is a spice.

Red is our salsa

on top of rice.

I love that the text rhymes and is restrained in length. Overall, the Spanish language words that were chosen were done so very carefully; they are mostly words that American children are likely to hear, if not at home then in an even modestly diverse community setting (ie. abuela). There are also plenty of culturally specific words (particularly food-related ones) that don't need translation since we use them in English, like churros or tortillas. Finally there are culturally significant terms that the author chose to introduce in English, like Day of the Dead. All these decisions were made with tremendous care.

Clarion Books (2012); hardcover, $16.99

Suggested target concept/word: immigrant

Laundry Day is a historically themed graphic novel-style picture book set in New York's Lower East Side in a bygone era of horse-drawn wagons, tenements, and crowded market streets.

A Jewish shoeshine boy, accompanied by his tabby cat, hustles for business on a crowded street, when suddenly a red cloth falls down from the sky. He looks up and sees laundry lines stretched out, criss-crossing between buildings, but no way to tell where the cloth has fallen from. He climbs balconies and fire escape ladders to find its elusive owner. Each person or family he meets is from a different immigrant group associated (at some point in time) with the Lower East Side neighborhood. They all see the cloth differently based on their background and we learn about their culture through that shift in perspective. (Incidentally, talking to a child about these shifts is a great way to practice theory of mind.) In the end, the boy returns the red cloth to Miss Fajah, a Jamaican seamstress who has enjoyed watching him search from the roof. It's her head scarf.

I first came across Laundry Day when I was looking for wordless picture books to read to my son Harry. Most of the panels in this graphic novel-style book don't have text. Books without many words are useful for kids who script because the words you use change each time you read it, and this helps prevent a child from reciting memorized lines rather than engaging with the story.

There are a lot of ways to approach talking about American immigration. But I think one value to a historical approach is that it sets up a foundation for understanding that this country is almost completely comprised of people whose families originally came from elsewhere. It doesn't appear anywhere in the text, but I am using this book to introduce the word immigrant.

One cautionary note is that the multi-panel graphic novel style is fabulous for developing sequencing and storytelling skills, but it can also be overwhelming visually for some children. This was the case for my son Luke, who had a much harder time attending to this book. I had some success using goal-oriented scanning ("Where is the cat?") as a way to help him focus. I also found that being careful to emphasize the repetitive plot structure, helped him find his place in the kaleidoscope of images.

Groundwood Books (2015); hardcover, $16.95

Suggested target word(s): totem animal, First Nations/American Indian

This exquisite little book by children's lit newcomer Danielle Daniel, a Métis writer and artist, introduces kids to the Anishinaabe tradition of totem animals. Daniel explains in an Author's Note:

Animal totems are also known as animal guides. In my book, a selection of totems act a guides to help children identify with the positive character traits of animals that may be familiar to them. Although children may associate with different animal guides throughout their life, it is commonly believed that one animal acts as their man guide. This connection can be shared through physical interaction, dreams, mutual characteristics or personal interest. The animal instructs and protects the child as they experience their physical and spiritual life.

Totem animals remind us that all living organisms are part of the same cycle of life.

Each page features one of Daniel's captivating paintings of a child dressed up as a totem animal. The repeating text, "Sometimes I feel like a..." begins a series of simple 4-line prose poems that describe some of the positive attributes of each totem animal.

Sometimes I feel like an owl,

intuitive and discreet.

I fly across the dark night sky,

always watching and listening.

For my son Harry, who loves animals, there was an immediate attraction to this book. I worked with him on how to pretend to be each animal and act out something in each description. For the above example, he flaps his arms to fly like the owl, puts his hand against his brow and pretends to look in the distance for "watching," and cups his ear for "listening." His pretending may be scripted and rigid, but I think these are the kinds of scripts he needs to learn to be more socially imaginative.

My son Luke enjoys naming the animals on each page. The repetition of "Sometimes I feel like a..." lets him know exactly when to fill in each animal name.

I am aware that this book isn't universally loved by First Nations (as they are called in Canada) and American Indian reviewers because it takes liberties in presenting totems as fluid identities that can be adopted at will rather than as rigidly inherited within clans and families. As a non-aboriginal person, I want to acknowledge that these disagreements exist, but I don't pretend to know enough to judge.

The way Daniel presents the totem animals of the Anishinaabe may not be strictly traditional, but it achieves a social-emotional end that is welcome in a picture book for children. Self-regulation and developing models of language to describe how you are feeling is a very big deal for kids on the spectrum—and many also obsess over animals, like my son Harry. When Harry is running around, but not being careful about where his body is crashing and landing, I can say, "Harry! Be a moose." The moose in Daniel's poem is awkward, but graceful and gentle, and when he hears this, Harry puts his thumbs up to his head to make antlers and, with deliberate gentleness, lumbers on.

Abrams Books for Young Readers (2010); hardcover, $16.95

Suggested target word(s): Mexico/Mexican, same/different

Duncan Tonatiuh is getting a lot of very deserved attention right now. His incredible picture book, Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote: A Migrant's Tale, is coming up more and more on book lists because it is so unbelievably important in this historical moment. It's a story, told like a fable, from the perspective of Pancho Rabbit, a child who pays a (literal) coyote to help him find his father who left on a journey to earn money in the lettuce and carrot fields and never came home. It's a brilliant, beautiful (and heart-breaking) book that is perfect for a child who is actively asking questions about the U.S./Mexican border and those immigration issues, but, unfortunately, it's way too complicated for kids like Luke and Harry.

However, I was thrilled to discover an earlier title by Tonatiuh, Dear Primo: A Letter to My Cousin, because it brings this author's critical voice to a less verbally advanced English-language audience.

Dear Primo goes back and forth between two boys: Charlie, in urban America, and his primo (cousin), Carlitos, who lives on a farm in Mexico. The boys are pen pals and they write back and forth and share stories about what their daily lives are like. For instance, the cousins compare how they get to school: Carlitos rides a bicicleta past perros (wild dogs) and nopal (cactus plants). Charlie takes the subway.

These exchanges reveal that the boys have lots in common but live their daily lives in exciting and different ways. At the end of the story they both come up with the same idea: their primo should come for a visit!

The ability to say what is the same and what is different is an important skill, and the parallel structure of this book is well suited for practicing it.

I don't think, however, that Dear Primo works as well for autistic children who don't live in a major city. I'm fairly certain that Charlie is from a place like New York City based on the scenes that are depicted. This matters because it is Charlie's life which gives us critical context for Carlito's. Charlie establishes the topic for each page: how we get to school, what games we play with friends, what we eat for dinner, etc., by showing the reader something known and familiar. But for a suburban American child, many aspects of Charlie's life are just as mysterious as life in rural Mexico (sparkling skyscrapers at night, playing in the spray of an open fire hydrant, the subway, etc.).

A parent could certainly tackle this by dialoging. For instance, if your child doesn't ride a bike to school (like Carlito) or take the subway (like Charlie), you could begin by asking "How do you get to school?" and helping your child say, "I take the bus!" or "Mummy drives me to school!" For some kids this may be too hard, while for others it may be excellent practice. It all depends on the child.

That issue aside, this is one of those books that can draw children in on the strength of its art alone. Tonatiuh describes his illustrative style as influenced by ancient Mexican art, the Mixtec codex. It is so, so pretty and gives a child a unique cultural experience on its own.

Dial Books (2005); hardcover, $17.99 USD

Suggested target word(s): Black/African-American, God/Jesus, spiritual

Kadir Nelson is a renowned artist who has illustrated many picture books for children but is also a notable painter whose work is exhibited in private collections and galleries around the world. His subject matter is African-American culture and history.

He's Got the Whole World in His Hands was an instant success with my kids. Good singalong books have a tendency to work particularly well when the song is highly structured or repetitive, has a strong rhythm, and is accompanied by vivid pictures that tie into the lyrics. This is the whole package.

"He's Got the Whole World in His Hands" is one of the most widely popular African-American spirituals. The back flap of the book explains:

...[S]pirituals are songs that have been passed orally from person to person or group to group and improvised along the way... The inspirational content of spirituals was crucial to the slaves who created them, and from this musical tradition was born gospel, blues, and jazz.

These are songs of faith and inspiration. Introducing them to children is a great way to begin to expose kids to African-American culture and its history.

The (capital-h) "He" that the song refers to is, obviously, Jesus, although I'm pretty sure that my kids think that it refers to the child on the cover of the book. This works for me at the moment as a fairly atheistic Jewish woman married to a non-practicing (but faithful) Catholic lady. I'm still puzzling over how to tackle religion. But for some families, this will obviously be a welcome opportunity to introduce or generalize words like "Jesus" or "God."

The book begins and ends zoomed all the way out, looking down at Earth from space. The child the book follows, a young African American boy, shows the reader a drawing of his family ("He's got my brothers and my sisters in His hands"), stands looking skyward in the pouring rain ("He's got the sun and the rain in His hands"), gazes at a full moon at night with his father ("He's got the moon and the stars in His hands"), fishes in rivers set against mountains, picnics in a park, swims in the ocean, and makes a puzzle shaped like the Earth with his dad. For the lyric, He has everybody here, in His Hands/He has everybody there, in his Hands, the boy and his family stand on a giant world map smiling from the Americas at a group of people on the African continent.

The repetition of the lyrics is enough structure on its own to keep my kids' attention, but the solid rhythm of the melody is also great for tapping to the beat. I slap one hand against the floor while I sing and both my kids really enjoy that and try to copy me.

Square Fish (2002); paperback, $6.95 USD

Suggested target word/concept(s): skin color

I spent a lot of time looking for a book that explicitly talks about skin color in a way that kids with autism can follow. This is the best I have found so far.

The Colors of Us is written from the perspective of a 7-year old girl named Lena, who is "the color of cinnamon." It is implied that she is mixed race since her mother has lighter skin ("the color of French toast"). Her mother is an artist and tells Lena that if she mixes red, white, yellow, and black paints they can make the right brown to paint a picture of Lena. Lena thinks "brown is brown," but Lena's mother tells her no, there are lots of different shades of brown.

On a walk, mother and daughter meet many of Lena's friends and greet adult members of her community who have a wide variety of skin tones. Some are contextualized in ways that imply a specific ethnicity, but this is not discussed explicitly. Lena observes how each one of them has a different shade of skin and compares each new color to something she is familiar with (mostly food): peanut butter, chocolate frosting, peaches, honey, fall leaves, butterscotch, pizza crust, amber jewels, ginger, toffee, etc. When she gets home, Lena mixes her paints to make all the different colors she saw and paints pictures of her friends and neighbors.

I love the artistic presentation of skin color difference as a way to introduce this concept. I think it works on a level that many kids can understand. The illustrations are very bold. The main pages that introduce each person are framed around the person's face, which I like a lot and gives the book a consistent structure. Luke had trouble with some of the more unique color descriptions (he doesn't know what cinnamon looks like), but I was able to redirect his attention by having him label parts of the face when this was an issue.

What The Colors of Us doesn't do is introduce commonly used racial categories based on skin color (white, black, brown-skinned, etc.). Instead, it explores a literal description of skin and color, which sends the message that everyone is a shade of "brown." This may be true when it comes to painting an accurate shade of someone's skin tone, but it isn't as useful as practical language for understanding race in America.

Nonetheless, I think this book is a very good place to start. The tight structure and focus on color labeling as a repeating plot device is accessible to autistic kids. And introducing the idea of "skin color" is critical to beginning a conversation about race.

HMH Books for Young Readers (2016); hardcover, $16.99 USD

Suggested target word: Latina/Latino

Maybe Something Beautiful is based on the true story of how an artist and community leader (husband and wife) transformed the once-dull East Village neighborhood in San Diego, California into the East Village of today, a predominantly Latinx community famous for its Urban Art Trail, a transformative mecca of murals and other community-based public art. The husband, Rafael López, who was the muralist who began it all, is also the illustrator of this incredible picture book.

The book tells the story of Mira, a Latina child who loves making and giving people art. One day she meets an artist painting a mural in her dull, gray neighborhood. They begin to paint murals together and everyone in the neighborhood joins in. There is a tense moment when a policeman shows up and Mira is sure they will be in trouble, but the policeman just wants to join in and paint too. While that moment may seem unrealistic to some, it seems to be based in the real experience of the artist and nonetheless provides an opportunity for parents whose children are developmentally ready to talk about the complicated issue of policing. All in all, it’s a powerful story about the power of art to build community and improve the livability of neighborhoods. Placing the brush in the hands of the little girl character sends a great message to kids about their own power to make change.

This is a book that averages around 50 words per page, so it’s definitely not appropriate for kids who have trouble attending to longer picture books. That said, López’ illustrations so clearly portray the action of the story, that there is a lot of potential to “read” this book by summarizing as you go. This is what I did with Harry. Once he “got” the story and began to appreciate the art I was able to read it fully with him attending. He really enjoyed the novelty of the occasional portrait spreads (you have to turn on the book on its side). He kept tilting his head as I turned the book.

Maybe Something Beautiful was too long and loosely structured for Luke to really get into, but he did enjoy naming the things Mira drew (a sun, tree, heart, flower, blue bird, elephant with a hat, green apple, and a red bird) and naming the colors of the paints the muralist and Mira used on the walls.

Beach Lane Books (2016); hardcover, $17.99 USD

Suggested target words/concepts: India/Indian, tuk tuk, Namaste, chai, poppadoms, Diwali, yogi, wala, rupees

The Wheels on the Tuk Tuk is the Indian twist on "The Wheels on the Bus" you didn't know you needed to complete your life.

A tuk tuk, for the unfamiliar, is a 3-wheel auto rickshaw that is used as a private vehicle, but also as a mass transit vehicle, in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Thailand, and other places.

The Wheels on the Tuk Tuk brilliantly centers an exploration of a small town in India around the familiar nursery song, instantly communicating with "Tuk Tuk wheels go round and round" that the tuk tuk is equivalent to a city bus. This basis for comparison is further cemented a few pages later when the "Rupees on the bus go ching ching ching."

It's next to impossible not to laugh when a cow sits down in front of the tuk tuk ("Tuk tuk stops for moo-moo-cow.") or when the "Elephant's trunk goes spray-spray-spray". (And the tuk tuk getting soaked with water naturally means that it's time to make the wipers go swish-swish-swish!)

My son Luke absolutely adores this book and loves to try to sing along with me. I love watching him take in this very different landscape of small town India, so beautifully rendered by the illustrator. It's clear to me he's studying it carefully. He loves the song, so it's his window into a variation on a familiar story. Variations on well-loved themes can be very appealing to kids on the spectrum.

You'll notice that this is the only book for which I have a very long list of words in my suggested target list. The reason for this is that the structure of the song is so particular and strong for practicing intraverbal skills (and the illustrations are so specific), that I actually think it's reasonable to imagine that you could teach a kid, even one who has fairly low language, that a poppadom is an Indian cracker, for instance. In learning each verse of the song and pairing it with the pictures, there is a strong basis for picking up and even understanding these new Indian words.

Sandpiper/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (2005); paperback, $6.99 USD

Suggested target word(s)/concept: Korea/Korean, chopsticks, bee-bim bop

If you've never had bee-bim bop (also spelled bibimbap or bi-bim bop or some other anglicized variation), you're missing out. The Korean word means "mixed rice." Traditionally, bee-bim bop is a bowl of warm steamed rice topped with sautéed vegetables, sliced cooked meat, and a fried egg. Gochujang (chili paste), soy sauce sauce, and doenjang (soybean paste) provide flavoring. Right before eating, everything in the bowl is mixed together.

This adorable picture book features a hungry and happy little girl super-pumped to help her mom prepare bee-bim bop for her family's dinner. They go to the grocery store, chop and prepare the produce, steam the rice, cook the vegetables and meat, set the table, assemble the bowls, sit down with the family, and use their chopsticks to mix everything together. Along the way there are all kinds of great opportunities to identify foods and objects in a kitchen and also to describe the actions of the girl and her mother (shopping, chopping, cooking, mopping, etc.). The family sitting down for dinner at the end is also a great model for the social skill of being part of a family meal.

But the number one reason this book is great for children with autism is that it has a seriously infectious beat and always ends each page with punching out BEE-BIM BOP!

Almost time for supper

Rushing to the store

Mama buys the groceries—

more, Mama, more!

Hurry, Mama, hurry

Gotta shop shop shop!

Hungry hungry hungry

for some BEE-BIM BOP!

Food is such a great way to help anyone connect to a culture. I love that this book actively encourages kids to take the journey a step further and make bee-bim bop!

The recipe at the end of the book has careful instructions that divvy up the cooking tasks into tasks for "you" (the child) and tasks for a grown-up. My kids are still a bit too picky for me to do this with them, but I know many young children with autism who are extremely picky and/or sensory eaters but who could make and eat some version of bee-bim bop. The most critical component is steamed rice. After that it's really up to you to determine which vegetable and/or meat to mix in (And whether to use an egg). Really any veggie or meat will do. Add a very light touch of oil, soy sauce, and sugar (with or without any of the spicier seasoning or flavors), and you have a passable introduction to this Korean dish.

If you want, you can even try to make eating it more fun by buying training chopsticks (if your family doesn't already use them). If your child has occupational therapy they've probably used chopsticks already, since OTs commonly use kiddie chopsticks to strengthen a child's grasp and practice fine motor skills. They sell ridiculously cute kiddie chopsticks with little animals and characters in many Asian food and supply stores. (They are also very easy to make yourself with takeout chopsticks, a small piece of paper, and a rubber band.)

G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers (2010); hardcover, $16.99 USD

Suggested target word: language

Uh-Oh! is one of my son Luke's favorite books right now, so I badly wanted to include a title by Caldecott honoree Rachel Isadora for this list. She is often compared to Ezra Jack Keats for her portrayal of a diverse cast of children characters in everyday life. Say Hello! is the book I decided to include for this list because it is so effective for showing a child what language is.

Carmelita and her dog greet everyone in her neighborhood on their way to her abuela's house. They all say hello to her in their native language. Carmelita learns to say hello in Spanish, Arabic, Hebrew, English, French, Japanese, Italian, and many other languages. Hilariously, Manny, her dog, seems to understand everyone, and says his version of hello ("Woof!") on each page.

Isadora's art is as amazing as always. This book uses a collage of cut prints mixed with oil paints, and the result is colorful and dazzling.

There is nothing complicated about this book at all, which is what is so great about it. One of the first things kids are taught in ABA is social greeting reciprocity (saying hi when someone comes over, etc.). This book does nothing but model that essential skill, repeating the social interaction of greeting over and over. This is great for generalizing greetings.

Some children may be ready to learn the name of the languages that are being used when people say "Hello!", but the important thing isn't to memorize that "Ciao!" is "Hello!" in Italian (although that's pretty cool), but rather to communicate the idea of language itself. This book really works well for that purpose.