Fairy Tales & Fables Part 1: Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Billy Goats Gruff, & The Three Little Pigs

There are so many reasons for parents to read fairy tales and fables to young

On a recent visit to my son Harry's classroom, I watched as he and his autistic peers were each told to describe a picture of a rock during a science lesson. One by one, they each held up a card showing a different rock—but with the picture facing themselves, not their classmates. When the teacher said to turn the card around so their friends could see too, many of them then turned it upside down instead of facing out.

Being aware that others have different beliefs, perceptions, or intentions is known as Theory of Mind. It develops in neurotypical children between the ages of 3 and 5. The autistic kids in my son Harry's class ranged in age from 5 to 8.

Some of the emerging research around Theory of Mind, shows how language acquisition impacts this area of development, particularly with so-called "false belief tasks." Understanding false beliefs is only one narrow element of Theory of Mind (and some think it's separate altogether), but it's important. The research tells us that whether or not a person knows and can use "mental state language" and its syntax is a prerequisite for mastering this particular skill.

Put simply: Does your child understand the meaning of words about the mind, like "think," or "believe" or "know"? This makes implicit sense to me: If we want our kids to be able to develop the skills of Theory of Mind, we need them to give them the tools.

Picture books are a great way to practice mental state language. A 2008 study found that 78% of picture books contain mental state language. But while almost any picture books have words like "know," there are some that put more emphasis on what characters are thinking about, their intentions, their false beliefs, and their feelings, both thematically and in their plotting.

Here are 10 of my favorites for flexing those Theory of Mind muscles.

Aladdin (1971); paperback, $7.99

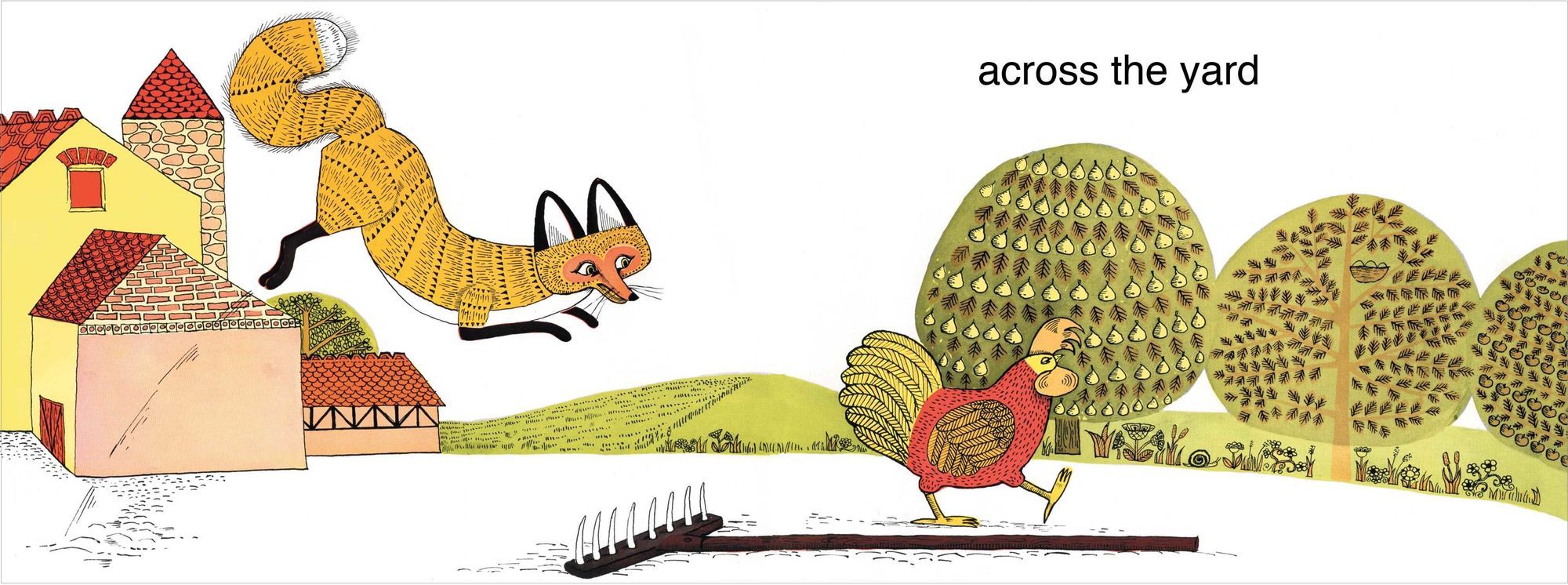

Rosie the hen goes for a walk, but she doesn't realize that a fox is stalking her. She is always mere inches away from being eaten when something disastrous (and hilarious) befalls the fox. In the end, the fox is chased off by angry bees, and Rosie gets home in time for dinner.

The most basic Theory of Mind skills can be practiced with Rosie's Walk. Rosie does not know she is being stalked by the fox because she never looks behind her. Likewise, the fox does not know it is about to have another Wile E. Coyote moment since it is only looking at Rosie and failing to notice the hazards that surround it.

This is also a great book for kids with limited attention. The entire story is pretty much one long sentence, chopped up into prepositional phrases. Even the line-heavy folk art ends up being just fine for easily overstimulated kids because Hutchins uses a limited, earthy palette and it all sits on a plain, white canvass.

My son Luke loves Rosie's Walk. It's a family favorite. He thinks the slapstick humor is endlessly funny, and enjoys saying "Rosie! Look out for the fox!" as we turn the pages.

G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers (1996); board book, $7.99

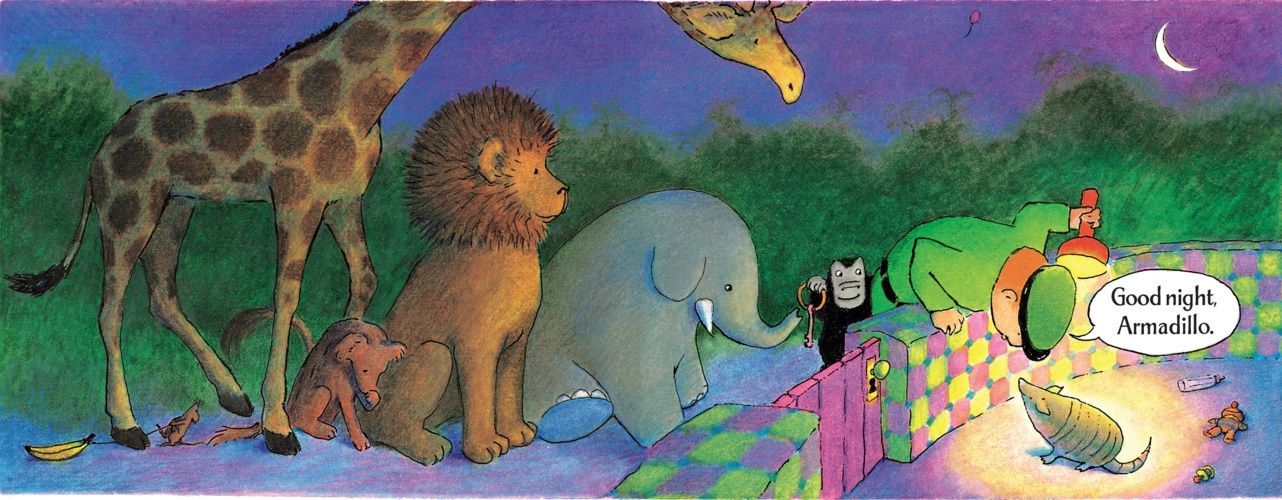

A zookeeper makes his nightly rounds, saying goodnight to all the animals—a gorilla, an elephant, a lion, and so on. But he doesn't realize that the gorilla has stolen his keys and is unlocking every animal's cage as he goes. A growing congo line of adorable zoo animals follow the zookeeper all the way to his own bed.

This is another easy example of the simple Theory of Mind concept of not being aware of what you cannot see. The zookeeper never turns around, so he isn't aware of the animals' mischief.

If you have a child who has trouble attending to books, you can first watch the super-cute (and inexpensive) animated short based on the book as a way to condition interest in it. I support using video media to increase interest in books and am firmly against screen-shaming. This multisensory strategy has worked well for my son Luke.

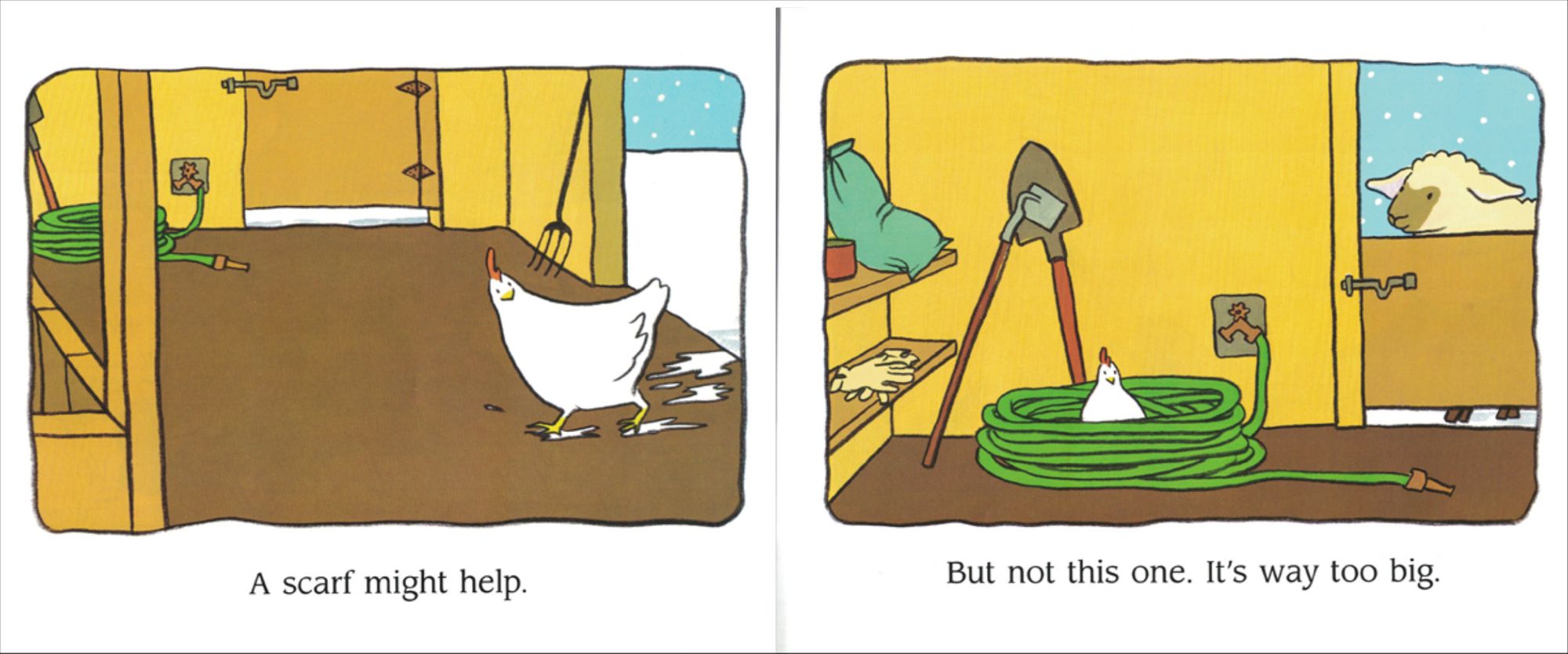

Puffin Books (1997); paperback, $6.99

Minerva Louise is a curious chicken who decides, one snowy day, to leave her coop and play outside. Spying a snowman dressed in warm outerwear she decides to look for her own winter clothes.

All of the Minerva Louise books are funny stories premised on the idea that the silly chicken never quite gets the human world because of her chicken-perspective. She finds a garden hose ("A scarf might help. But not this one. It's way too big.") and a pair of gardening gloves ("And these boots are too big, too."), and then decides that what she really wants is to find the perfect hat.

Minerva Louise's quest is sure to get a lot of laughs. Simply told with crisp illustrations, A Hat For Minerva Louise is an excellent book for exploring false-beliefs and point of view in a silly way that kids will enjoy.

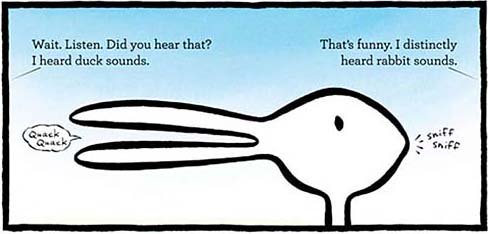

Chronicle Books (2009); board book, $16.99

This simplified line illustration of the classic Duck-Rabbit illusion is basically The Dress for kids. And just like that hideous dress (it was white and gold), the illustration of the duck/rabbit lets you explore how differences in perception can frustrate. When I read this with my twins, I purposefully "see" whatever animal my sons don't see at first.

In Duck! Rabbit!, two people (not shown) argue back and forth about whether the creature before them is a duck or a rabbit. The thick, black line drawing of the duck/rabbit against a spare blue background stays basically the same throughout the book, but Lichtenheld adds bits of detail and context to show us the unseen debaters' points of view.

Because the illustrations shift to give context to the differing perspectives, kids should easily see how the drawing can be seen as both a duck and a rabbit. I love how Duck! Rabbit! demonstrates how our perceptions can shift. And indeed, in that spirit, the people arguing in the book switch sides in the final pages as they begin to see the other person's point.

An optimistic rabbit and a pessimistic rat are having a picnic. Rat sees only problems as the story progresses (it rains, the umbrella breaks, apples fall on their heads, there is a worm in the apple, etc.), while Rabbit is able to look for the bright side (an umbrella when it rains, a tree for shelter when the umbrella breaks, an apple to eat when it falls from the tree, a cake in the picnic basket when the apple is wormy, etc.).

Jeff Mack's cartoon graphical style is easy on the eyes, and the action is easy to follow. The choice to use only the words "Good news" and "Bad news" is a perfect jumping off point for talking about what is happening and how the two animal friends see it differently. The repeating plot cycles are easy to follow and allow a child to settle into the rhythm of the story.

The book ends with Rabbit finally cracking and seeing that things are indeed quite bad. His tears prompt Rat to realize his gloomy outlook has made his friend sad, and he turns things around. The sun comes out and the two enjoy their picnic at last.

Two Lions (2014); hardcover, $16.99

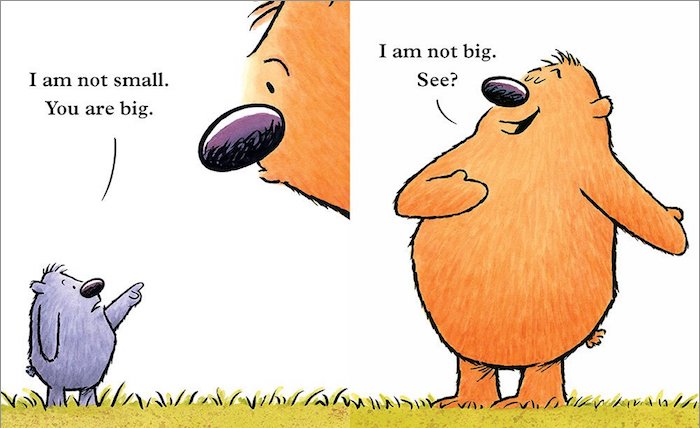

A small purple creature and a large orange creature have a very funny shouting match in this exploration of point of view based on relative size. The small purple creature insists that it is not small, the orange creature is just big! The orange creature insists that it is not big, the purple creature is just small!

Further complicating things (perhaps too much for some kids) groups of the orange and purple creatures show up to support their side of the argument, and finally a giant creature and miniature creatures arrive on the scene too.

You Are (Not) Small lends itself well to funny voices and lots of giggling. The cartoon illustrations against the white backdrop are an ideal visual choice. Full marks for this cute story that is fantastic for exploring point of view.

Chronicle Books (2016); hardcover, $16.99

I remember standing in a bookstore reading They All Saw a Cat for the first time and thinking, This is going to win the Caldecott. It did, and my excitement hasn't waned.

A child's pet cat is seen through the eyes of a dozen creatures as we turn the pages of this captivatingly illustrated exploration of perspective taking. The cat looks like lunch to a fox, but renders as an oversized monster to a mouse.

Perspective isn't just about one's place in the food chain; it's about one's biological and environmental differences, too. The bee sees the cat as a collage of dots through its compound eyes, while the goldfish's watery view is blurred from below the surface of a pond.

My son Harry is enthralled by every page because the art is so gorgeous and varied. Some kids who are more visually sensitive may not love how loud and busy some of the pages are, however.

As a read-aloud They All Saw A Cat sings;. Wenzel has a perfect grasp of how to use repetition, pacing, the meter of prose poetry, and the careful arrangement of typographic elements.

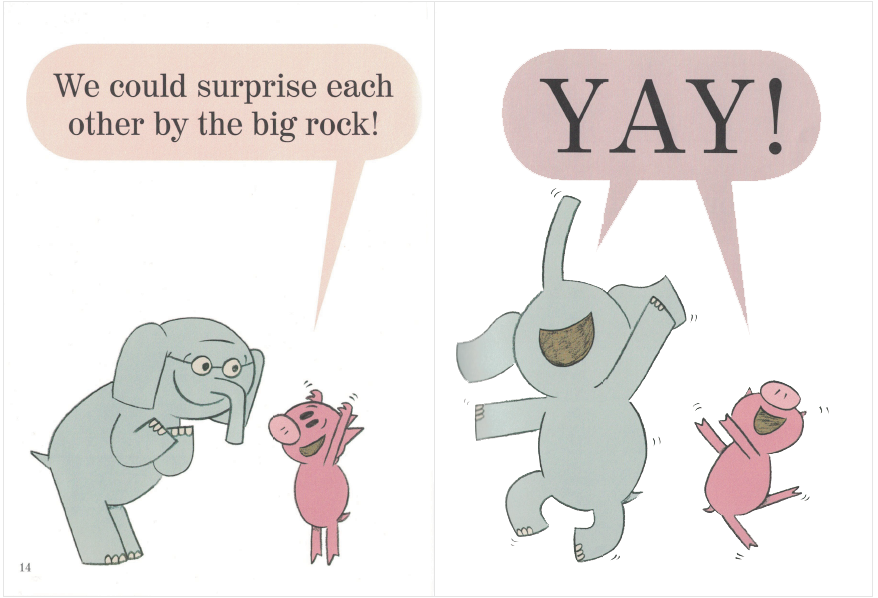

Hyperion Books for Children (2008); hardcover, $9.99

One of the best ways to represent that people all have their own internal mental states is visually—through cartoon thought bubbles. And probably no author does that better for younger children than Mo Willems.

I could have chosen almost any book by Willems for this list, but I like I Will Surprise My Friend, an Elephant and Piggie series title, because the plot is a slightly more advanced theory of mind concept: the second-order false belief.

This is pretty academic, but basically a first-order false belief is when someone has a false belief about something concrete (John thinks the box is empty—but it's not). While a second-order false belief is when someone has a false belief about what someone thinks about something (John thinks that Mary thinks the box is empty—but she doesn't).

The plot of I Will Surprise My Friend! is trackable even if you don't follow the mental state plot, but it has examples of this. Elephant and Piggie decide it would be fun to play surprise. They decide where to surprise each other (a rock) and both sneak towards the rock excited to surprise their friend. (There is some great Theory of Mind humor just in this silly set-up!) Then, they each sit on their side of the rock waiting for their friend to show up to surprise them, and imagining what the other person is doing and thinking (incorrectly). Of course, this culminates in them actually surprising each other!

Don't let my academic spiel scare you away from Elephant and Piggie books. I promise that the plots are trackable and very funny even if your child isn't able to figure out the mental states right away. That is in fact why I recommend them! These books make fantastic read-alouds and children universally love the characters and silly stories.

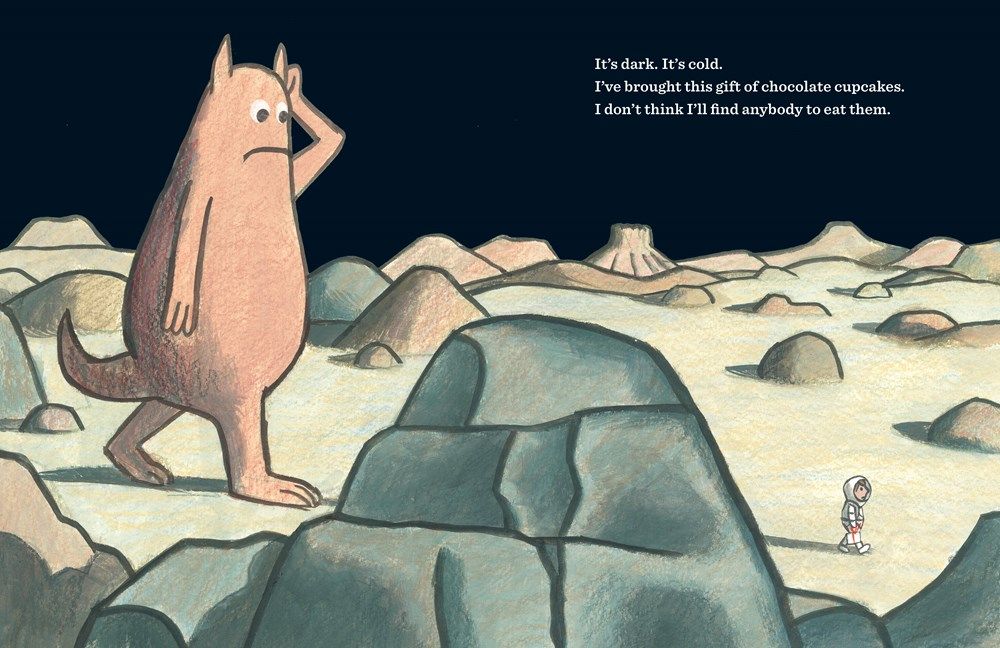

Dial Books (2017); hardcover, $17.99

A boy astronaut arrives on Mars in search of life. He wanders the planet, dejected at finding nothing, unaware that a huge, orange Martian creature is following him curiously. Adorably, he has brought a box of cupcakes as a gift for any life he might find. He loses the box briefly and finds it again. It is revealed in the end that the alien ate the cupcakes, much to the boy's surprise.

In developmental psychology, there was a very famous study of developmentally delayed children called the "Sally-Anne" experiment. The research is from 1985, but it is the basis for a lot of what we understand about Theory of Mind deficits in children with autism today. In it, two dolls are introduced (Sally and Anne) to a child subject. The child watches a skit in which the Sally doll takes a marble and hides it in a basket. She then leaves the room, and while she's away the Anne doll moves the marble to her own box. When Sally comes back in, the children being studied are asked where Sally will look to find her marble. The researchers found that most children with Down's syndrome were perfectly capable of understanding that Sally would look where she left it, while most children with autism would guess that Sally would look in Anne's box.

In Life on Mars the plot point about the chocolate cupcakes is remarkably on the nose as a Sally-Anne test. The reader sees that the alien has taken the cupcakes and replaced the empty box, but the boy thinks the gift box still contains cupcakes. On the spaceship ride home, the reader is therefore supposed to anticipate the moment when the boy looks inside the box and realizes that something on Mars ate the cupcakes. If we understand his surprise, we have passed the Sally-Anne test.

The art in this book is lovely and simple–black skies frame a beige and gray-shaded planet surface, sculpted with thick brown lines. Life on Mars is one of my personal favorites.

Puffin Books (2002); paperback, $12.95

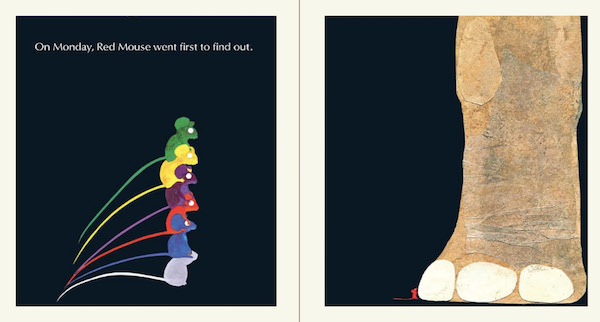

Seven blind mice, each a different color, investigate the "Something" that has shown up by the pond. But each mouse explores only part of the Something, and so comes to the wrong conclusion. Red Mouse imagines the elephant's foot as a tall pillar. Green Mouse imagines the elephant's trunk as a huge snake. And so on.

In the end, White Mouse explores the entire Something and realizes that it's an elephant.

This is an almost perfect book. It is unnecessarily complex in parts—including days of the week for no reason, and not sticking to a uniform syntax. But the plot is repetitive, the collage art pops wonderfully against a solid black background, and the use of color to show what the mice are imagining (the tail becomes a blue rope when Blue Mouse guesses the Something is a rope, for instance) is extremely clever.

Seven Blind Mice is fantastic for practicing the mental state language related to imagining and guessing. It is also a wonderful allegorical way to explore why a diversity of perspectives is important.